The data of the space telescope contain the traces of many unknown celestial bodies

With a sophisticated combination of human and artificial intelligence, astronomers uncovered 1701 new asteroid trails in archival data of the Hubble Space Telescope spanning the past 20 years. While about one third could be identified and attributed to known objects, more than 1000 trails probably correspond to previously unknown asteroids. These unidentified asteroids are faint and likely smaller than asteroids detected in ground-based surveys. They could give the astronomers valuable clues about conditions in the early solar system, when the planets were formed.

In June 2019, on International Asteroid Day, an international group of astronomers launched the Hubble Asteroid Hunter, a citizen science project on the Zooniverse platform. Their goal: to visually identify asteroids in archival data from the Hubble Space Telescope.

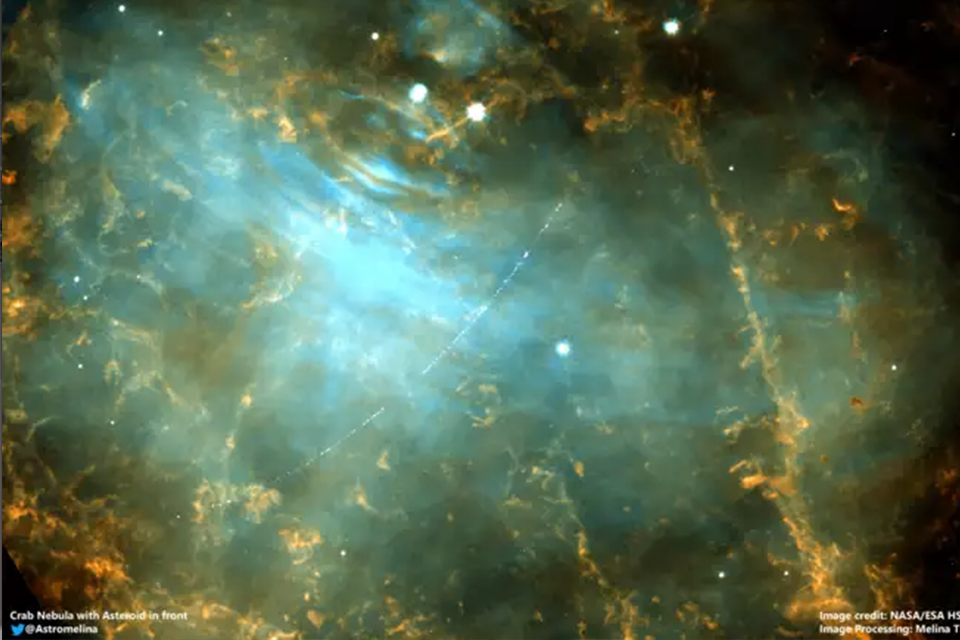

“One astronomer’s trash can be another astronomer’s treasure,” teases Sandor Kruk, now at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, who led the study. Most of their sought-after data is removed automatically in other observations campaigns as noise. “The amount of data in astronomy archives increases exponentially and we wanted to make use of this amazing data.” Taken between 30 April 2002 and 14 March 2021 with the ACS and the WFC3 cameras on-board the Hubble Space Telescope, the astronomers identified more than 37 000 composite images pointed all over the sky. With a typical observation time of half an hour, asteroid trails should show up as streaks on these images.

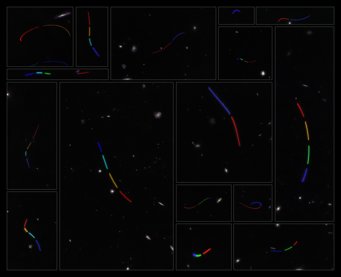

“Due to the orbit and motion of Hubble itself, the streaks appear curved in the images, which makes it difficult to classify asteroid trails – or rather it is difficult to tell a computer how to automatically detect them,” explains Sandor Kruk. “Therefore we needed volunteers to do an initial classification, which we then used to train a machine learning algorithm.” In numbers: There were 2 million clicks on the Hubble Asteroid Hunter webpage, 11 482 volunteers provided 1488 positive classifications in about 1 % of the images. The astronomers used these classifications by the citizen scientists to train an automated machine learning algorithm on Google Cloud, to look for additional asteroid trails in the remaining archive data. This led to another 900 detections and a total of 2487 possible asteroid trails in the Hubble archive data.

Three of the authors, Sander Kruk, Pablo García Martín from the Autonomous University of Madrid, and Marcel Popescu from the Astronomical Institute of the Romanian Academy, inspected these trails, excluding cosmic rays and other objects, which led to a final dataset of 1701 trails found in 1316 Hubble images. Of these, about one third could be identified as known asteroids in the Minor Planet Center, the largest database of Solar System objects, leaving 1031 unidentified trails.

A positive identification as an asteroid (with a known orbit) will need further observations, but the sample already looks very interesting: These objects are systematically fainter and therefore probably smaller than typical asteroids detected from the ground, with a similar speed and distribution on the sky as the known asteroids in the so-called Main Belt. In follow-up work, the astronomers will use the curved shapes of the trails imprinted by the motion of Hubble to determine the distance to the asteroids and study their orbits.

“The asteroids are remnants from the formation of our solar system, which means that we can learn more about the conditions when our planets were born,” explains Sandor Kruk. “But there were other serendipitous finds in the archival images as well, which we are currently following up. Using such a combination of human and artificial intelligence to scour vast amounts of data is a big game changer and we will also use these techniques for other upcoming surveys, such as with the EUCLID telescope.” “Although it was designed to image galaxies, EUCLID is estimated to observe 150,000 objects in our Solar System,” adds Rene Laureijs, Project Scientist of EUCLID and co-author of this study.