Linguists and computer scientists collaborate to publish a large global Open Access lexical database

Scholars from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany and the University of Auckland in New Zealand have created a new global repository of linguistic data. The project is designed to facilitate new insights into the evolution of words and sounds of the languages spoken across the world today. The Lexibank database contains standardized lexical data for more than 2000 languages. It is the most extensive publicly available collection compiled so far.

Is it true that many languages in the world use words similar to“mama” and “papa” for “mother” and “father”? If a language uses only one word for both “arm” and “hand”, does it also use only one word for both “leg” and “foot”? How do languages manage to use a relatively small number of words to express so many concepts? An interdisciplinary team of linguists, computational scientists and psychologists have created a large public database that can be used to study these and many more questions with the help of computational methods.

"When our Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolution was founded in 2014, I presented my colleagues with an ambitious goal: there are more than 7000 languages in the world. Create databases with the most extensive documentation of the linguistic diversity as possible," says Max Planck Director Russell Gray. "Our inspiration came from Genbank – a large genetic database where biologists from all over the world have deposited genomic data," Gray continues. "Genbank was a game changer. The large amount of freely available sequence data revolutionized the ways we can analyze biological diversity. We hope that the first of our global linguistic databases, Lexibank, will help start to revolutionize our knowledge of linguistic diversity in a similar way."

New standards and new software

The Lexibank repository provides data in the form of standardized wordlists for more than 2000 language varieties. "The work on Lexibank coincided with a push towards more consistent data formats in linguistic databases. Thus Lexibank can serve both as a large-scale example of the benefits of standardization and a catalyst for further standardization," reports Robert Forkel, who led the computational part of the data collection. "We decided to create our own standards, called Cross-Linguistic Data Formats, which have now been used successfully in a multitude of projects in which our department is involved".

The new standards proposed by the team are accompanied by new software tools that greatly facilitate linguists’ workflows. "We have designed new computer-assisted workflows that enable existing language datasets to be made comparable," says Johann-Mattis List, who led the practical part of the data curation. "With these workflows, we have dramatically increased the efficiency of data standardization and data curation.”

Identifying patterns of language evolution

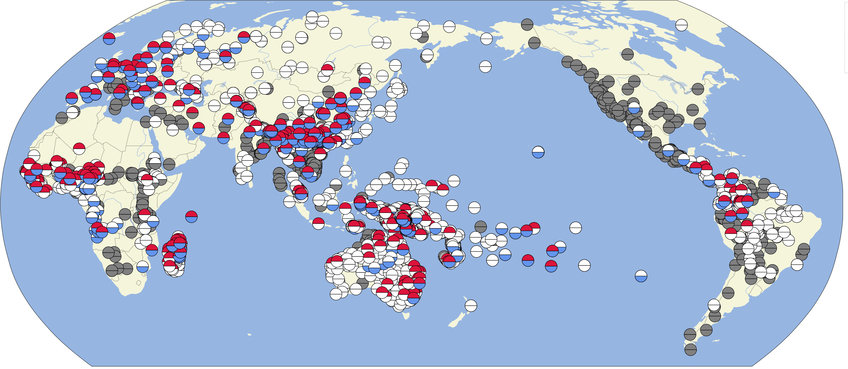

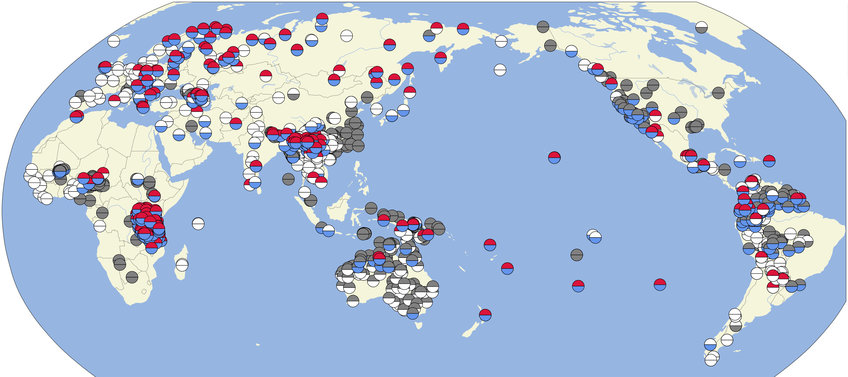

In addition to collecting and sharing the standardized language data, the authors also designed new computational techniques to answer questions about the evolution of linguistic diversity. They illustrate how these methods can be used by computing how languages differ or agree with respect to sixty different features.

"Thanks to our standardized representation of language data, it is now easy to check how many languages use words like‘mama’ and ‘papa’ for ‘mother’ and ‘father’,” reports List. "It turns out that this pattern can indeed be found in many languages of the world and in very different regions," adds Simon J. Greenhill, one of the founders of the Lexibank project. "Since all the languages with this pattern are not closely related to each other, it reflects independent parallel evolution, just as the great linguist Roman Jakobson suggested in 1968".

Expanding the data and developing new methods

The new data collection, and the automatically computed language features will contribute to new insights into open questions on linguistic diversity and language evolution. “Nobody thinks that the analysis must stop with the examples we give in our paper,” says List. “On the contrary, we hope that linguists, psychologists, and evolutionary scientists will feel encouraged to build on our example by expanding the data and developing new methods,” adds Forkel.

Even in their current study, the authors present findings that warrant future investigations. “When investigating which languages use the same word for ‘arm’ and ‘hand’, we found that these languages typically also use the same word for ‘leg’ and ‘foot’,” List reports. “While this may seem to be a silly coincidence, it shows that the lexicon of human languages is often much more structured than one might assume when investigating one language in isolation”.