An alarm system against hardware attacks

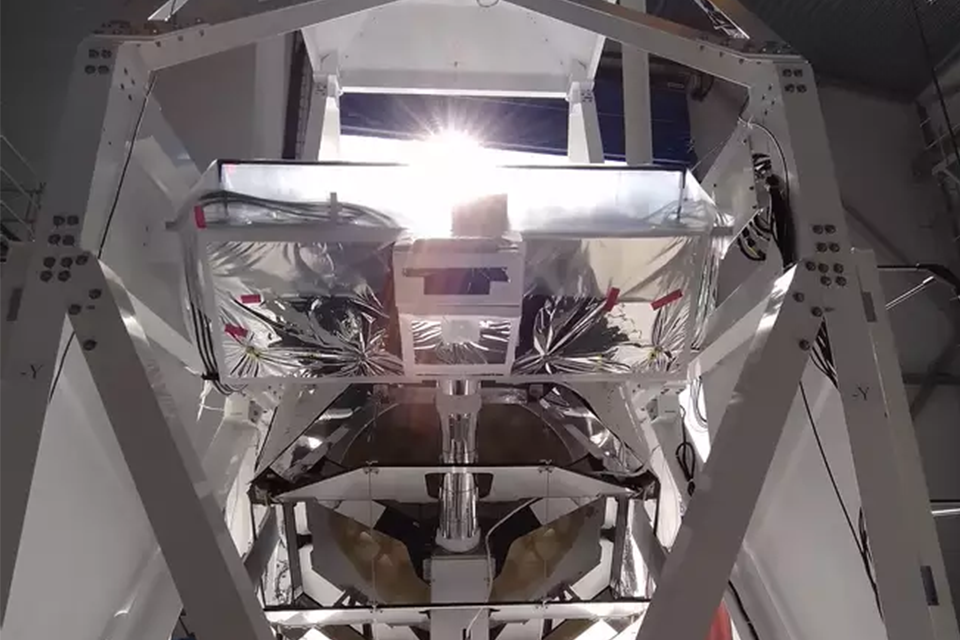

Radio waves could protect computers, as well as card readers, from attacks on their hardware. As a team from the Max Planck Institute for Security and Privacy in Bochum and the Ruhr University in Bochum has shown, the signal from one antenna in a device generates a characteristic electromagnetic pattern that is received by a second antenna. If an attacker manipulates the device with a wire, for example, the radio wave pattern changes and blows the whistle on the manipulation like an alarm system.